“If you are a plastic surgeon or dermatologist and you take a photograph of their face using your phone, you’re not capturing fine lines and details. This means that you’re losing treatment options of what that patient might get from your practice, which becomes a feedback loop, a financial one too.”

~ Woodrow Wilson, CEO and founder of Clinical Imaging

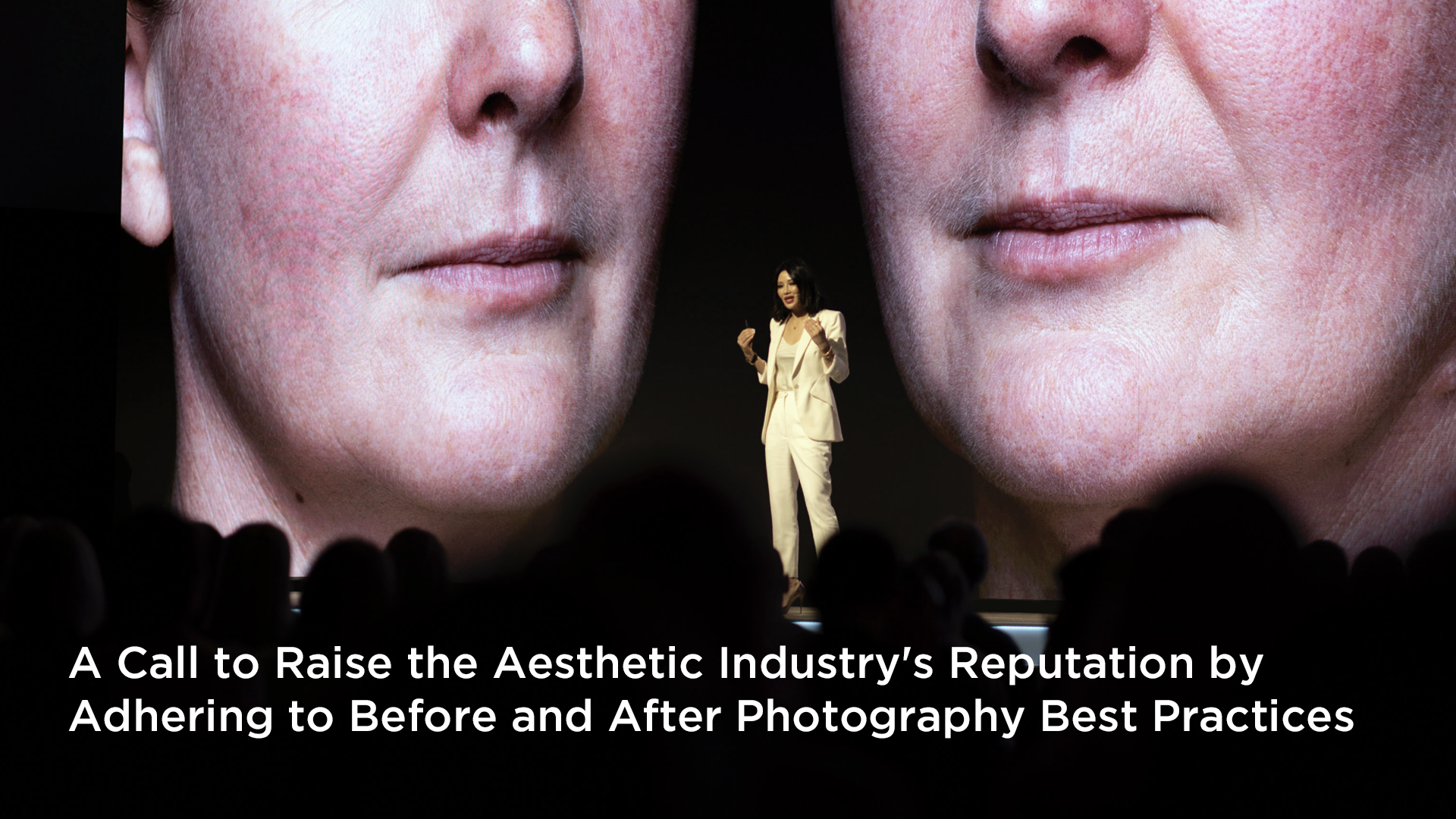

Woodrow started as a conference photographer in 2012, when he saw a professor lecturing at a plastic surgery Congress and was shocked by the contrast between the scientific knowledge the surgeon spoke of and the lack of scientific evidence in the before and after photos he presented on the screen showed.

That led him to found Clinical Imaging Australia. There, he put his photographic expertise to the test to create a photo-taking system that is 1) easy to use, 2) produces consistent quality photos, and 3) has a very short learning curve. Today, they have 140 clients in nine different countries across many different specialties.

The system has evolved continually since then, but basically, its cameras, lighting, and software are amalgamated in such a way that it resembles what a commercial photographer would use. To take any guesswork out, it has a pre-calibrated camera and a lighting system that makes it easy for non-professional photographers to capture consistent quality images.

To encourage the use of best practices in taking before and after photos and for full disclosure, Woodrow’s hope is that societies and congresses adopt a rating system so when a surgeon speaks on plenary, the images show a quality rating and are labeled as an A, B, C, D or F.

Photography is basically imaging physics. The first problem he generally sees is that if you are too close to a subject (or using the wrong hardware), the photo will be distorted. If you are too far away, it has distortion. There’s a middle ground that’s just right. The second problem is color, which relies on lighting. The Clinical Imaging System standardizes these two variables so you end up with a perfect photo without distortion and the right color that shows skin tone in order to identify their proper Fitzpatrick classification.

The last aspect of best practices in before and after photography is data management, which really is time management. For this, you need a system that organizes your files into patient folders and properly named files that are stored on the cloud, are secure, and have two-factor authentication. This way, those who are allowed to see these photographs can see them very quickly and easily, and those who don’t want to see them have no chance of getting access to them.

As with any scientific endeavor, it’s all about reducing the number of variables in taking before and after photographs. The only thing that should change is the patient.

To manage the lighting variable, the Clinical Imaging System attaches studio strobes to the ceilings so that they come down at a 45-degree angle. This angle creates three-dimensionality to a face or to a body. You can only do that when you’ve got angled light. This uses science in your favor. The strobes send out a pulse of light that completely freezes whatever the camera is focused on and produces a good, stable, sharp image.

The next variable is patient and camera placement. Instead of using an overlay grid to get a reproducible angle, it uses science by aligning anatomical planes and by using the electronic spirit level. This is basically a “level” on their cameras that tells you if the camera is parallel to the ground and shows the distance and height of the subject, giving you input to make any adjustments necessary.

For example, if we’re taking a photo of the face, we overlap it with the Frankfort plane, which goes from the tragus through the bottom of the infraorbital ridge to the tip of the nose. Once you overlay those two things, you solve all the problems in terms of your distance, your height, and your angle.

There is no need for a ghosted overlay because you’re doing the same process each time, whether you’re photographing rhinoplasty or lips. You’re aligning the Frankfort plane.

So then you don’t need tripods; you don’t need C stands or floor stands. You don’t need umbrellas, you don’t need soft boxes. It also makes the photography area less intimidating for patients because they do not walk into what looks like a professional film set.

Woodrow recommends thinking twice before snapping a photo with your phone. It’s quick and easy, for sure, but they’re exchanging time now for time in the future. That file is not properly named, and there’s no name, and there’s no data security. In addition, if it’s on your personal device and you lose it on the way home, you’ve got to remotely wipe that photograph. This might lead to losing many months’ worth of cases. That’s not the sort of professionalism that a clinician should bring to their patient experience at all.

Other problems with iPhones, iPads, Samsung, or other phone cameras are image size and detail. People look at a 15-megapixel camera and think it’s a good size. But what matters is not the megapixels, it’s the size of the sensor in the camera. Bigger sensors have larger photo sites, and they collect more light, color, and higher fidelity information.

Another danger of a smartphone is that it can have a really biased interpretation of skin tone and skin detail. When you look at a photo taken with an iPhone, you probably notice that everyone looks a little bit better than they do in real life. That’s because they’re trying to even out the skin tones or the exposure versus a really bright background. And the photos all look amazing, but it’s not reality. We need to be dealing with reality in a clinical setting.

It’s good that there are systems available in the US, but you need to know what you are getting. For example, TouchMD Snap is a tablet-based system with some really good ghosting tools, but from a technical point of view, they still take photos on a phone or an iPad. Despite all the marketing you get from Apple or Samsung, they are still light years behind what a mirrorless or an SLR camera can perform. It’s science. It is what that device is able to capture.

RX photo, again, is a phone-based system, so the same things apply.

Canfield Intelli Studio is an impressive piece of equipment, but its major problem is lighting. The light source is mounted on the device, and the patient is standing in front of it. That light source is perpendicular. When you have a light source that’s perpendicular to an object, you fill that object’s crevices and all the topography of that face, flattening the image.

The other thing to consider is if the system is a walled garden so that your data is locked away. If so, you can be sure it will be hard and maybe even expensive to take your photos with you if you decide to change vendors.

Woodrow recommends looking for an open-source method that uses industry-standard JPEGs and raw images produced by the camera and stores them on a cloud storage service like Microsoft OneDrive. This allows users to store, share, and access files from any device. Then, when you need a file, you can grab it quickly, or if you need to share it, you can share it quickly.

In summary, doctors often don’t realize the cost associated with not having good photography. In Woodrow’s experience,e it costs them from the first day they open a private practice all the way to their last.

- First, it’s a medical record and needs to be part of their medical journey for legal purposes.

- Secondly, scientific objective photography is needed to do a thorough consultation.

- Lastly, potential patients can’t tell all the amazing things that you’ve studied and the years of experience you have by looking at poorly taken before and after photos.

The aesthetic industry needs scientific objective photography of each and every patient to use as their medical record and with the proper release in a practice’s marketing and as a consultation aid. When you use your phone or an iPad to take a photo, you’re exchanging time now for time in the future. Quality before and afters don’t cost; they provide the biggest opportunity a surgeon has in their practice.

*A “spirit level” is a small, built-in bubble level that indicates whether the camera is perfectly horizontal (level) when taking a picture.

This article was written by Candace Crowe of Candace Crowe Design to help those wanting to learn more about how to take better before and after photos. The content for that article was taken from a podcast with Woodrow Wilson, a Melbourne-based photographer and CEO of Clinical Imaging.

You can listen to the full podcast by going to https://candacecrowe.com/blog/the-crowes-nest-podcast-episode-11/

To learn more, go to: https://www.clinicalimaging.com.au/howitworks or

http://www.instagram.com/clinicalimaging_systems/

Resources: 32031-a-standardised-system-of-photography-to-assess-cosmetic-facial-surgery